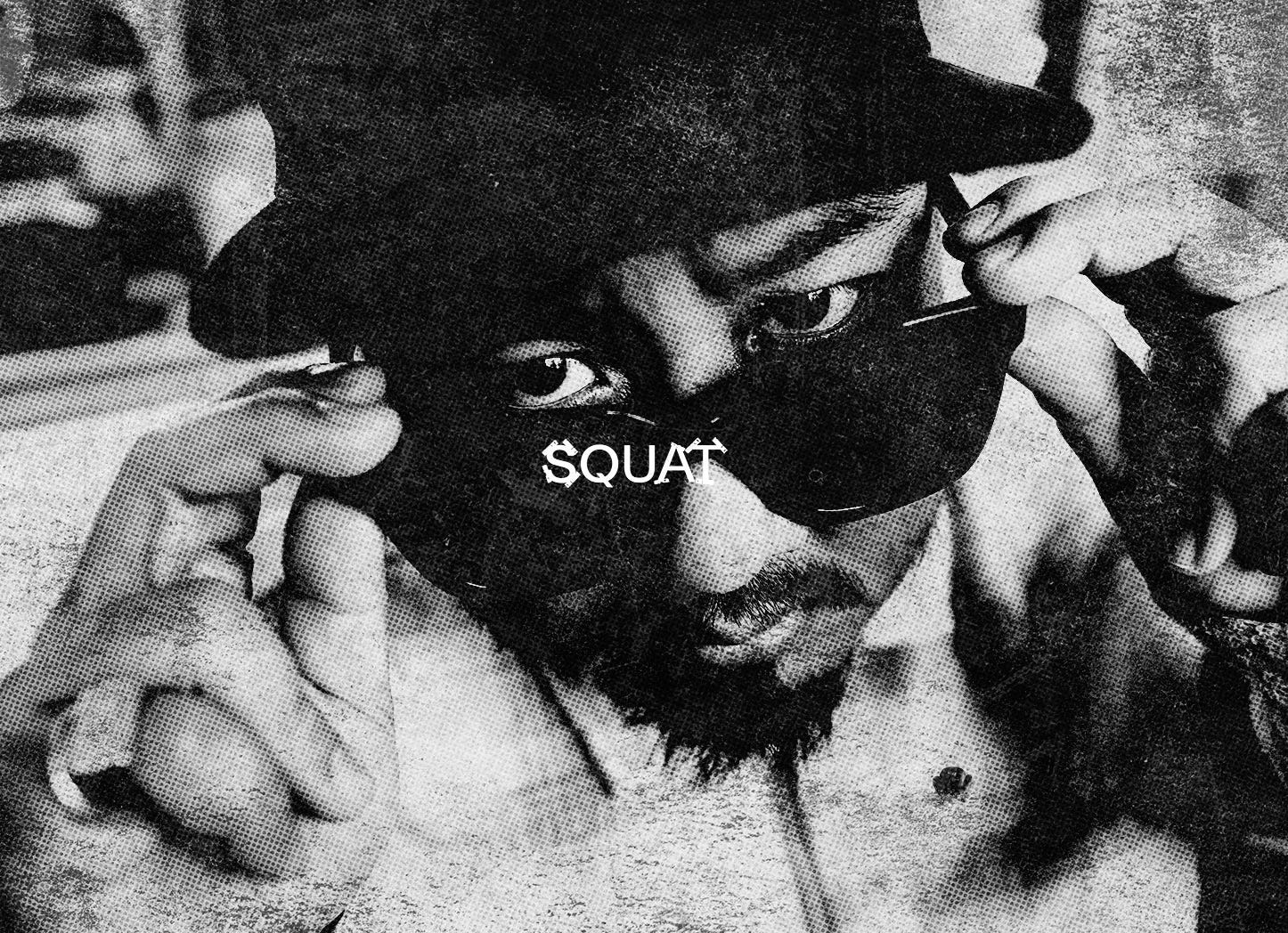

From the Mud We Still Bloom: Johnny F. Kim on Vulnerability

Getting angry, cold showers, and learning how to be in your feelings

JOHNNY F. KIM HAS A ROUTINE. He’s at the gym most early mornings. After working out, you’ll find his progress pics on Instagram stories standing squarely in front of the mirror (usually in the same position).

Fridays, you’ll see him at LOPEZ, a skate and streetwear joint in Montreal. “He usually just talks shit,” Denis, who co-owns the shop, tells me.

Weekends are with Amy, his daughter. And, in his spare time, he’s usually up to something. And, by something, that’s generally one of many niche interests.

Outside of his day job, Johnny is, for lack of a better word, a multi-hyphenate. His middle name, “Farovitch” (a Hebrew name), was a name his father found in a book and claimed as his own when immigrating to Canada. His last name, “Kim”, seems more Korean than Khmer. Vocationally, He’s a video producer—DJ (“most legendary scratchers are Filipino,” he tells me)—videographer—podcaster—cement sculptor—streetwear designer—and he is probably pretty good at playing pool.

All these interests stem from his need to explore and express his vulnerabilities. With Uneducated Kids, his streetwear label—Johnny likes to think of it as a personal memoir—an ongoing journey of discovering a past largely removed from his (and his community’s) history.

I’m sitting with Johnny at Café Larue & Fils for a catchup as he tells me about his latest capsule drop: a hat embroidered with the words “Mekong Night Club” that serves as a personal ode to the historic venue and the legendary Khmer singer Ros Serey Sothea.

“This was me trying to find remnants of the past of these mythical venues where music and art were showcased,” says Johnny, who does most of his research by reading the scarce resources online and by watching documentaries like Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten: Cambodia’s Lost Rock and Roll (2014).

Before the Khmer Rouge, the 60s and 70s were a hub for Cambodian garage and psychedelic rock—creative genres that have since been lost in time but not forgotten.

Today, there’s a small punk and hardcore scene in Cambodia, supported by young upstarts trying to go against the mainstream like DOCH CHKAE and the now-defunct SLITEN6IX (“I didn’t even know there was a punk scene until you shared it,” Johnny says).

It all boils down to the need to express—whether in the motherland or on Canadian soil—and the need to share stories.

“We need to be sharing how we can all relate to each other’s generational trauma and survivor mentality,” he says.

“It’s okay to feel a certain way as Cambodians because we all have this tragedy with our people.”

The following is a conversation with Johnny F. Kim. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

NIKKI: So, how've you been? I hear you've been going to the sauna now.

JOHNNY: Yeah, I do 25 minutes. And then I take a cold shower.

NIKKI: I hear that improves your mood.

JOHNNY: I feel like I'm in heaven. I could literally pass out at the gym.

NIKKI: That's a good way to destress. I think we need ways to do that. With Khmer folks, you've gone through experiences where the trauma is much more present.

JOHNNY: It's from our parents and the war. It just carries on, and it lingers.

NIKKI: It's very hot (very present).

JOHNNY: Is it?

NIKKI: Yeah, I mean, with Filipinos, we've gone through, like, over 400 years of colonization and imperialism from the Spanish, the Americans, and a little of the Japanese.

But we've had time to decompress. For you guys, it's—

JOHNNY: It's like the 70s, like what...75–79?

NIKKI: It takes time to get past trauma.

JOHNNY: I mean, we've seen it. We've heard about it. Our parents, they've talked about it. Now there's a new generation that's trying to figure out what to do about it.

When they came here, they had nobody. Like, that's the thing with Cambodians. A lot of them didn't have a choice.

How do we make the culture grow from the pain? That's why with Uneducated Kids, the slogan "From the mud we still bloom" [shows our resilience].

Because with the regime, they tried to erase it—our culture. So, we take whatever's left and push it more to make it better because we can't hold on to much. We have to evolve at some point.

NIKKI: That's where the saunas and cold showers come in.

JOHNNY: That's me! That's just me, you know. I try to find things that make me feel better.

NIKKI: I think we need ways to feel better, for sure. For the muscles and the mental. Speaking of mental, I've been talking to a lot of people about Beef.

JOHNNY: So good. I spoke to my friend Tim about the angry side of it.

NIKKI: Right, like, how would you define your anger? Were you an angry kid?

JOHNNY: It was a thing I kept in. I'd just explode. You know how some people are more like, "I'm always angry?" It builds up, where things keep adding on, and then things get nuclear.

NIKKI: And what happens?

JOHNNY: I'd lose it. I'd black out, haha.

NIKKI: Any stories?

JOHNNY: I told this one in the Weird Feelings podcast. One time in Grade 3, I cut the line for ice cream, and they caught me. They told me to go back to the line, and I got mad.

I wanted ice cream right away and started crying. Some kid came up to me and asked me why I was crying, and I punched him.

NIKKI: Right.

JOHNNY: I think it happened cause he saw that I was vulnerable. I've been able to tame it. But it still builds up. Now I go to the gym, and it gets out. My anger right now is more about how things are in society right now and how we're perceived as immigrants. We always have to work harder. You always have to prove yourself.

We're supposed to be sharing our feelings, but that didn't happen until we got older. Before, it was just like, "Shut up and go on with your day." And that stuff affects us in the long term.

That's why, with Beef, I connected more with Danny's side. It's like he's always trying to prove to his parents that he's not a loser. He's trying to make things work for his family. Then you have Amy, she's successful, but to herself, she doesn't feel like it's enough.

It's that weird dynamic of proving yourself to your parents and other people and proving yourself to yourself.

NIKKI: Yeah, I mean, with Daniel, I really identified with his character because I did a lot of that petty shit when I was younger. I say that I'm angry all the time because I think that's better than having all that built-up rage.

When I was younger, it would just come out at random times. I'd break walls. I'd break a lot of things.

JOHNNY: Because you didn't know how to express.

NIKKI: I couldn’t express myself! And like, when it comes to like petty shit, like, I used to steal all the time. From different people. Different businesses. I stole from all these people because I have a little bit of something to help myself feel better.

If I was at a job that I hated, I'd piss in the fucking sink. Like this wasn’t okay.

JOHNNY: So petty *laughs*

NIKKI: Like, dude, I was peak Danny until I was [22]. It wasn't good. Not good.

One of my friends is going to therapy, and I said even said that line from the show, "Western medicine doesn't work on Eastern minds." So, if I ever got help, it'd have to be from an Asian psychologist who also put in the work.

But anyway, with my friend, they've realized that having intense emotions isn't necessarily good. So, rather, having them as a constant, it kind of levels out.

JOHNNY: I feel like it comes down to how we're parented. How Asian parents tell us we're not supposed to show emotions.

We're supposed to be sharing our feelings, but that didn't happen until we got older. Before, it was just like, "Shut up and go on with your day." And that stuff affects us in the long term.

NIKKI: The thing is, a lot of our hang-ups stem from this sort of survival mechanism. The way we talk, what we're expected to do...I feel like the expectations are very salient with you folks because it's so present.

JOHNNY: When they came here, they had nobody. Like, that's the thing with Cambodians. A lot of them didn't have a choice. Everyone went into survival mode, where they had to raise the kids and make sure there was a roof and food on the table.

I try to talk to my parents about their dreams. It's kind of hard, and they don't really tell me. They have these repressed dreams they don't tell because too much happened, and it's hard for them to express it.

NIKKI: When did you first realize it was okay to be in your feelings?

JOHNNY: Good question. Maybe during the pandemic? That's when everybody started to reflect. There were a lot of conversations around that time about how it's okay to talk about our feelings.

I'd say a lot of my reflection was about trying to do all these things and working them out. Now I'm more self-aware about my actions and how I do things. My podcast Weird Feelings helped a lot—especially when it comes to just talking about things.

NIKKI: Right. I think I've been more comfortable opening up post-pandemic. My entire life, people have opened up to me. It's only recently that people started asking me how I'm feeling.

JOHNNY: You're like a barber.

NIKKI: Yeah, but I don't cut hair.

Uneducated Kids “Mekong Night Club” capsule will drop on Friday, May 19, 2023, at LOPEZ in Montreal, QC, Canada.